Before Jam was born, the world went to war. Not against each other but against monsters, people who did terrible things to others and those who permitted them to operate. A few people, later called angels, led the revolution and destroyed or locked up the monsters, often having to act monstrously themselves. Now there is peace and happiness.

In the town of Lucille, Jam, a selectively mute transgender Black girl grows up believing everything is perfect. After all, the town slogan is “We are each other’s harvest. We are each other’s business. We are each other’s magnitude and bond,” taken from Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem Paul Robeson. There is no hatred, no bigotry, no abuse. Or so they say. But Lucille isn’t a utopia for everyone. For some it is a monster’s playground, for others their own private hell. The monsters aren’t gone, they just learned to hide.

When Jam accidentally cuts herself on one of her mother’s new paintings, she inadvertently summons a creature from another world. Pet, as it calls itself, is hunting a monster preying on the family of her best friend, a boy named Redemption. But the identities of the victim and the predator are still unknown. Pet’s hunt will force the teens to confront truths they never wanted to know and expose the lies the townsfolk have been telling themselves for years. Torn between Pet’s deadly vengeance, Redemption’s rage, her parents’ willful ignorance, and a town that won’t listen, Jam must decide what is justice, what is right, and what must be done, even when those three things don’t agree.

Emezi plays with dialogue in unexpected and challenging ways. Jam is selectively mute, meaning sometimes she speaks out loud and other times uses sign language. With Pet, Jam can communicate telepathically. Emezi denotes her speaking voice with quotation marks and sign language with italics. And when she and Pet speak with their minds, Emezi uses no punctuation marks whatsoever. On top of that, dialects, phrases, and cultural traditions from across the African diaspora (Trinidad, Igbo, African American Vernacular English, etc.) are peppered throughout, giving a sense of realism and honesty. The resulting effect is a sumptuous, colorful book where the dialogue is as poetic as the narrative text.

If you need to have every detail explained, then you’re going to have a hell of a time with this story. Emezi offers few specifics or reasons for anything, not where Lucille is located, not where Pet comes from or the science behind its appearance, nothing. Nada. Naught. No way. No how. And honestly? I loved it. Trying to explain the hows and whys and wherefores would have diminished the work and lessened its impact. I wanted to know more, of course I did, but not knowing everything didn’t detract from the story. If anything, it kept me more focused on Jam, Redemption, and Pet.

Lucille’s angels did terrible things to root out the monsters once before, but now the town faces a different kind of problem: how do you find a monster when monsters aren’t supposed to exist? At one point Jam asks an adult “What does a monster look like?” But no one can give her a real answer. When she examines paintings of angels from a library book, they look like what a child might think a monster looks like. As does Pet, for that matter. Pet, the creature Jam’s parents are terrified of. Pet, with curving horns and hidden face and Jam’s mother’s severed hands. Pet, the creature from another world come to hunt and kill in ours.

If monstrous looking creatures can behave monstrously without being monsters, then what does an actual monster look like? As Jam and Redemption learn the hard way, they look like everyone else. Real monsters are just people. They don’t lurk in the shadows but walk in sunlight. They are friends and family and neighbors and teachers and coworkers.

As an adult, I can sympathize with Bitter and Aloe. I don’t have children, but I understand wanting to protect your child and keep them safe. They weigh the danger to Jam against whatever is happening to someone else’s child and the stability and sanctity of Lucille; even though choosing Jam isn’t the best course of action, it is a safe one. They remember the time before the monsters were locked away and the pain and violence it took to make Lucille a sanctuary. But for Jam and Redemption, discovering that the monsters never really went away shatters their foundation. It means their parents aren’t perfect. Jam and Redemption haven’t yet learned to ignore the hard questions in favor of the easy answers. When history repeats itself, they must become their own angels.

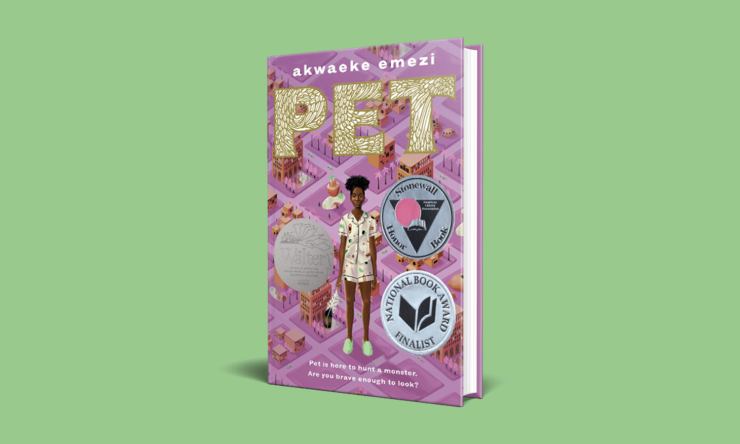

Like Emezi’s first novel, Freshwater, their YA debut Pet defies all attempts at categorization. It’s young adult skewed toward tweens but with some decidedly adult subtext. It’s fantasy that feels like magical realism mixed with a science fictional future. Stylistically and tonally, the closest YA author comparison I can think of is Anna-Marie McLemore—both write gorgeous, lyrical stories about diverse queer characters—but even that misses the particular Akwaeke Emezi-ness of Pet. But why waste time trying to force Pet into a box when you could just surrender to the experience? It is what it is, and what it is is pretty much perfect. This is a novel that must be read and shared.

Buy Pet From Underground Books

Or Explore Other Great Indie Bookstores Here!

Originally published in September 2019

Pet is available from Make Me A World

Alex Brown is a high school librarian by day, local historian by night, author and writer by passion, and an ace/aro Black woman all the time. Keep up with her on Twitter and Insta, or follow along with her reading adventures on her blog.